The curators proposed to look through the eyes of England in the second half of the nineteenth century as a site of discussion and experimentation related to color. As a result, the result is a big picture, in which along with art, fashion and design there is a place for philosophical debates, scientific discoveries, travel and shopping.

The organizers of the exhibition say that there is a common stereotype that the Victorian era was all black or gray. It is believed that her palette was formed from the smoke of steam locomotives and boiler houses, coal dust and Queen Victoria’s mourning dress, which she wore for 40 years without taking it off. Charles Dickens in his novel Hard Times wrote: “It was a city of red brick, that is, of brick that would have been red if smoke and ashes had let it (…) It was a city of machines and tall chimneys from which endless snakes of smoke curled from century to century. The city had a black canal and a river whose water was mixed with purple bad-smelling dye.” The exhibition opens with a full-wall print of a reproduction of a Gustave Doré engraving in which London looks like a large black-and-white machine, delineated by a grid of pipes and fences. This intro is sort of ground zero, after which begins a colorful and exciting refutation of a boring stereotype.

The story of the Revolution of Color begins with the story of the collaboration between painter William Turner and art theorist John Ruskin and their shared love of Venice. It was Venice, with its blue lagoon, sunshine and colored houses, that revealed to these two Englishmen the beauty of color. The exhibition opens with Turner’s luminous Venetian landscape, in which the sun sparkles and is reflected in the blue surface of the water, and the walls of colorful houses literally dissolve in the stream of light. Reskin himself considered Turner the best colorist, and considered color in nature to be a divine gift. And by the way, it was Reskin who began to praise color in painting, putting it above the laws of composition and drawing and thus anticipating the discoveries of the Impressionists.

Another place of attraction for artists was France with its cathedrals and stained glass windows. In 1855, Oxford students Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris traveled to France, where for three months, like medieval craftsmen, they walked from city to city and cathedral to cathedral, studying the shining legacy of the Middle Ages. The Victorians shattered clichés about the gloomy and barbaric Middle Ages by revealing the vivid colors of stained glass windows and manuscripts: fiery reds, lemon yellows, shimmering ultramarines. An entire section of the exhibition is devoted to the effect this discovery had in art and design. There is a stained glass window by Burne-Jones, gold tableware reminiscent of Merovingian art, a casket resembling a relic, and bookplates framed in gold ornamentation, written in Gothic script and decorated with delicate illustrations.

While Ruskin and the artists close to him raved about the Middle Ages and read in the colors of nature the presence of God, scientific knowledge was rushing forward. Charles Darwin developed a theory of the origin of species in which color, stripped of its divine connotations, was a key condition for the continuation of life, linked to the instinct to reproduce and attract a mate in birds or a pollinating insect in flowers. In the second half of the nineteenth century, news from the world of science became part of popular culture: lectures, textbooks and illustrated encyclopedias were accessible and interesting to a large number of ordinary people.

Artists began to use scientific knowledge in art: flowers and leaves were depicted as if they were viewed under a microscope. Frederick Sandys depicted the enchantress Vivienne surrounded by a fan of peacock feathers, with bells and poppies, and John Everett Millais detailed the foliage and gold plant ornamentation in his portrait of Marianne. The symbol of the wonderful natural beauty and color harmony was the rainbow. Her images and references in the exhibition are constant: in book illustrations, paintings and quotations from Victorian texts.

Artists, in turn, also participated in the creation and classification of scientific knowledge: Scottish artist Patrick Sim and geologist Abraham Werner produced a detailed catalog of flowers. They gave names to each hue and indicated where that color is found in the animal, plant, and mineral world. Charles Darwin used this catalog to describe exotic animals. Thus, the color revolution has affected language by enriching it with many new definitions.

The fascination with the natural world was reflected in design (there is a separate showcase devoted to it at the exhibition) and jewelry art: for example, bird feathers and beetle wings were used to decorate fashion accessories. That explains why one of the most unexpected pieces in the exhibit is a necklace made from hummingbird heads. Jeweler Harry Emmanuel chose 7 birds of different colors, gilded their beaks and replaced their eyes with colored stones. From afar, the product seems to be made of large stones and only when you get closer, you realize the horror of what is happening. The number of birds and insects killed for the fashion industry is horrifying: hundreds of thousands of hummingbirds were sent to England every week to decorate hats or become part of a piece of jewelry.

A truly revolutionary change was the invention of artificial dyes in 1865, when William Henry Perkin, a chemistry student in London, accidentally produced a bright purple color from coal tar. Coal tar was a waste product of the British coal and gas industry – that’s why it was cheap. The ability to extract color from a material that had previously been associated only with smoke and dust seemed like a true miracle. Contemporaries wrote, “To get a rainbow from a lump of coal seemed as improbable as extracting sunlight from cucumbers.”

Colored clothing, which used to be very expensive and was a symbol of status and wealth of its owner, is now available to almost everyone. After Perkin’s discovery, it wasn’t 10 years later that fabric was learned to be dyed in many different colors. Technological and fashion innovations quickly spilled over to the continent. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the number of shades derived from synthetic dyes numbered in the hundreds. The exhibition shows a catalog of German fabrics and threads from 1900, whose brightness and variety are as good as modern fabrics. The love for colored clothes had by then turned into a real passion: everything was dyed, right down to petticoats and underwear. Even English men, accustomed to dressing in dark clothing, began to add brightly colored socks, vests, or neck scarves to their closet. Often colored were their home clothes, such as the flower-embroidered house slippers shown in the exhibit.

In sculpture and ceramics, the majolica technique was particularly popular at this time. Objects of various purposes, from dishes to fountains, were coated with paint laced with lead. This metal made the colors more intense and made them shine and shimmer in the sun. The poisonous properties of the material soon became known, which caused a very high mortality rate among manufactory workers. By the end of the XIX century majolica was no longer produced, so that this shimmering colors of art and remained the property of the Victorian era.

Colorful was the art of the British colonies: colorful Indian and Middle Eastern fabrics quickly became fashionable, feeding a perpetual thirst for the exotic. The Middle East and Egypt were the first popular destinations for Victorian tourism. Artists, armed with paints in tubes (a technical innovation of the 1840s), set out on journeys, seeking to gain new experiences and enrich their ideas about color.

Not only the present but also the distant past has taken on color. Antiquity came closer through archaeological excavations and the activity of agents sent on search expeditions by British museums. Remnants of colored pigments on Greek sculptures also testified that these sculptures were once brightly painted. Subjects from ancient history became popular in art: the luxury and scope of events of ancient kingdoms warmed the imagination of the Victorians, and in the citizens of ancient Greece they often saw themselves. It is no coincidence that the artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema depicted the sculptor Phidias scaffolding atop the Parthenon in front of the painted metopes (treasures of the British Museum since 1817). Phidias receives visitors in much the same way that a Victorian painter might have received guests and customers in his studio.

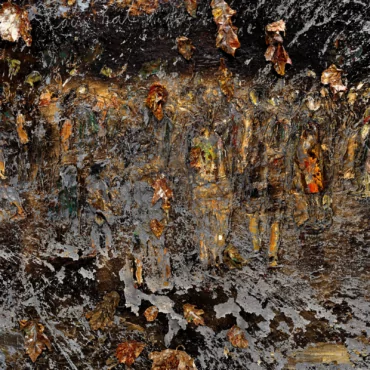

By the 1870s, the role of color became so high that artists began to talk about its self-value. Color was no longer seen as evidence of a divine presence in the world (Ruskin) or a tool for attracting a mate (Darwin), but existed on its own without any applied function. Oscar Wilde believed that “pure color, unspoiled by content and not associated with a particular form, can appeal to the human soul in a thousand different ways”. The exhibition shows the work of James Abbott Whistler: the outline of St. Mark’s Cathedral peeks through fields of blue, gold, and gray. Here there is no place for the meticulous precision of the Pre-Raphaelites – color goes beyond the shores of contours, filling the space of the canvas and becoming the main character of art.

In the late nineteenth century, some colors were given symbolic connotations. Yellow and green, for example, were associated with decadence. The latter, which resembled the color of absinthe, often indicated the mental confusion or social marginality of the paintings’ protagonists (Eugene Grasset’s “The Morphinist”). For example, in Ramon Casas’s “Decadent Woman. In Ramon Casas’s “Decadent Woman After Dancing,” the green sofa and wallpaper are just as eloquent a sign as the reclining pose of a lady tired of entertainment. The book’s yellow cover suggests that it’s the heroine reading a French erotic novel, a forbidden but popular piece of literature that was going around at the turn of the century.

Finally, the color revolution was reflected in emerging technologies – photography and electrical special effects. The curators tell the story of two extraordinary women working at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Dancer Loye Fuller of the Folies-Bergère bar in Paris, dubbed the “fairy of electricity,” began using colored spotlights in her dance performances, anticipating many trends in modern dance and theatrical lighting.

The second heroine, Sarah Angelina Acland, was a pioneer of color photography. The exhibition concludes with a shot of her with a rainbow. This rainbow in the last hall seems to unite all the previous subjects of the exhibition: it is a reminder of divine love, and the desire of scientists to “unravel” the color spectrum and catalog each hue, and about Hokusai’s prints, inspiring the British, and the technological miracle of extracting colors from a bar of coal tar. The rainbow photograph seems to draw a line under the romantic, daring and narcissistic 19th century. The color revolution is complete, and the unknown and alluring 20th century looms ahead.

The exhibition runs through February 18, 2024 at the Ashmolean Museum.

Loading...

Loading...