On one of the sites on the Internet you can find classic black and white photographs: panoramic views of St. Petersburg and Venice, landscapes of Iceland, portraits of famous artists and strangers. The photos seem to come to the viewer from a beautiful world of the past, but little is said about the photographer: born in Leningrad, he shoots with classic cameras, uses large and extra-large format.

Behind this modest description is Vadim Levin, the former first deputy chairman of VTB, whom the Russian and world press has called “one of the most influential top managers of the bank” and “a personal friend of Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin.

Seven years ago, Vadim Levin settled in England. We stopped by his house to see his camera and photo collection and talk about how his life changed when he stopped being a banker and became a photographer.

How did your passion for photography begin?

How’s that? Back then, in the Soviet Union, everything was simple – parents took to the club at the Pioneer House. That’s where we took our very first photos, developed and printed them ourselves. The process of the image appearing in the bathtub, in the red light, made a strong impression – I remember it to this day. I still have a Soviet-made black tank for a ruble for developing film.

How many cameras do you have now?

Honestly, I didn’t count. I don’t collect cameras and lenses – I have all of them, as they are called, working ones. In general, I have cameras of all formats, starting with a narrow format “Leica” and ending with a 12-by-20-inch format camera. Years ago, when I first printed a portrait shot on an 8-by-10 camera, I thought, why did I take so long to photograph on other cameras? This kind of plasticity, depth and detail cannot be achieved on smaller formats. A photograph taken on a large format creates the full illusion of volume. However, the mobility of large-format cameras is significantly inferior to their smaller counterparts. In general, the presence of many cameras is more of a disadvantage than a plus. I, for example, have a wonderful Rolleiflex with old optics. It was the main camera of three of the greatest photographers: Irvine Penn, Richard Avedon and Helmut Newton. They shot all of their major masterpieces with “rolleyflex,” which have become classics of world photography. I, unfortunately, never learned how to shoot with this camera. A good rule of thumb is to concentrate on one camera rather than jumping from format to format.

As a child, did you think you would pursue photography seriously?

I shot all the time: both at school and at university, and even in construction camps, I found the opportunity to develop film and print cards. But when I went to work, things got a lot more complicated.

Did you run out of time?

Catastrophic. For eight years I worked in Moscow in a very intense regime: from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m., including most weekends. At that time, I wasn’t really interested in photography. I started out at Vnesheconombank (VEB), which was the government’s agent for foreign debts. And the government traditionally worked on weekends, and the deputy prime ministers held endless committees on Saturdays, where they simply invited everyone. They weren’t at all interested in who had what work plans. And, I remember, you sit in the White House for half a day and wait most of the time for a pretty meaningless meeting. And then I had to do real work and deal with a topic that was new to me.

Was that in the early 2000s?

Yes. In 1997 I went to Moscow and worked at VEB until 2002. Then I moved to Vneshtorgbank (VTB), where the situation was different. VTB at that time bore little resemblance to a real bank, and almost everything (structure, procedures, regulations) had to be created practically from scratch. I was fortunate enough to have had banking experience, although on a completely different scale. But it was all insanely interesting. Much was done for the first time and was managed largely in manual mode, where everything depended on the ability to make decisions and take responsibility.

What do you mean “in manual mode”?

All major transactions were structured individually, taking into account the requirements of clients, on the one hand (and the struggle for large customers was very serious at that time), and the requirements of regulations – on the other. It was very important not to overstep the reasonable boundary of risk, without which there is no financial transactions in principle. I was less interested in the banking routine, although I was probably one of the few top managers who understood the operational processes. I started almost from the bottom, so at least I understood how the bank worked.

Who did you start out as?

Deputy head of the operational department of the Imperial Bank branch in St. Petersburg. I was called there in the early 1990s by a fellow student with whom I was in graduate school. That bank is long gone. Everyone remembered him only for his commercials, which were brilliant. Nevertheless, I learned a lot of things there.

And from there you were already invited to Moscow?

Yes. A few years before Imperial, I met Alexei Kudrin, the future Minister of Finance of Russia; he and I are still friends, by the way. He invited me to the bank.

Was it difficult to move from St. Petersburg to Moscow?

I guess so. I am, after all, a very St. Petersburg person. St. Petersburg is a city that lives in a completely different rhythm, much more relaxed. In Moscow, even time went by differently. This has always amazed me. When I finished working in Moscow, I decided not to stay there.

Did you finish it on your own accord? Weren’t you sorry to leave such a high position?

No pity. There were different circumstances. In 2007, I had a rather complicated surgery in Germany. I miraculously survived. After that I worked for two more years, but I could no longer work in the same mode. I’d come in from meetings at 11 p.m. and I felt like I wasn’t physically going to last that long. In addition, VTB had a strategy of becoming more Western, and I was a member of the previous generation. And that’s wrong, too. A lot of what I did at the bank was good for its time. Then came people much more educated, more technologically advanced, and better suited to the moment.

During your time at VTB, is there anything you’ve done that you’re proud of?

VTB, on my initiative, financially supported a number of major projects in Russian industry. I think they were good deals, and time has confirmed that. On the other hand, seeing how many successful banks of the first wave went bankrupt because of non-performing loans, I have convinced at all levels that the so-called kickbacks most often end badly for people and are always detrimental to the bank. Along with the achievements, there were annoying mistakes that could have been avoided.

How did you end up in London?

My son went to a good grammar school in Moscow, but in St. Petersburg he went to a regular school, where he quickly went from A’s to C’s. I don’t even want to think about the atmosphere in that school. One day he asked: “Dad, can I go to England to study?” I said okay. He passed his exams as best he could then and went. Two years later, my daughter and I also moved to London.

Weren’t you bored here at first?

No, I was never bored, because I went straight into photography. And then, when there are a lot of kids, there’s always something to do.

Do you see photography more as a new career or a hobby?

Good question. I have a serious project in St. Petersburg – a gallery and photo lab called Art of Foto. The laboratory is very well equipped, I think it’s one of the best in Europe. In addition, we have assembled a very strong team of professionals. So to some extent photography is a business for me, albeit on a small scale.

Profitable?

So far, not so much. We’re trying to get into the black, but it’s not completely successful for a variety of reasons. First of all, because we are constantly growing and expanding. Just recently, for example, we installed a unique magnifier that has no analogues in the world. In the studio, we have a 20-by-24-inch camera – there aren’t many of those in the world, either.

Why business in St. Petersburg and not London?

First of all, everything is clearer to me in Russia. And then I don’t see a market for classical photography here. London is mostly interested in modern art and contemporary photography, and that’s not my thing.

Why classical photography?

I love classical art – that happens, too. As for contemporary art, I would say this: if I don’t understand it, why would I pretend to understand it? I am generally skeptical about modern photography. A very typical example is Andreas Gursky. I’ve seen his work live, but no one can convince me that it’s a masterpiece. Let’s say “Beaches of Rimini” is a three-meter photo canvas. I know roughly how much it technically costs to make it. About $5000 you can manage (sold at auction for £585,000 – note ZIMA). What is the masterpiece of Rimini’s beaches? What’s the concept? Are there a lot of people on the beach? I don’t know. And the notorious “Rhine II” (the most expensive of the photographs sold, $4.3 million – note ZIMA) I’m not even talking about. Still, commercial success – and Gursky is undoubtedly super-successful – is not, to me, an indicator of the artistic level of a work. It all reminds me more of show business. I hope that fans of his work will not take offense at me too much.

What principle do you use to select photos for your collection? Focusing on collectible value or personal taste?

When buying, I am guided primarily by personal taste. There are things I just like. There are those that you like less, but they cost adequate money, and there is no risk that they will drop in value over time. The important point that distinguishes photographs from, say, paintings, is not the uniqueness of the work. Each photo has an edition, usually from 8 to 30 prints. Another significant factor that greatly affects prices is the time it takes to create a print. Collectors greatly value so-called vintage prints that were made with a short interval of time from the shooting itself. For me, vintage plays almost no role at all, on the contrary, the older the print, the greater the risk that technologically (fixing, washing, archival toning) it was not made very correctly, which could affect its preservation.

In addition to the specifics of the photography market, there are also general laws. Sometimes the pricing is incomprehensible to me. Here, for example, is Helmut Newton’s famous photograph Sie kommen, in which models are dressed and naked. Separately, each of the two photos is not so expensive, but a pair is already unrealistic money in my mind. Some of the pictures of Rodchenko, whom I love very much, I can’t afford either. But I did buy a portrait of Mayakovsky. This photograph, despite its small size, is an amazing example to me of the perfect composition for which Rodchenko was famous.

What is the most expensive work you have in your collection?

Probably Richard Avedon’s portrait of Marilyn Monroe.

How much is it worth?

About £100 ,000. This is a work I really wanted to have in my collection. A portrait of Picasso by Irwin Penn costs a similar amount of money.

Do you exhibit your own work? What kind of fate would you want for them anyway?

There was one solo exhibition at the GRAD Gallery in London. There were several exhibitions in Provence. In St. Petersburg I participated in two joint exhibitions in our gallery: “Roofs of St. Petersburg” and “Yards-Wells. We published a book based on them. The next exhibition will be on a close theme – “Parades of St. Petersburg. It would be ideal to show these works in one of the Hermitage buildings; we are trying to arrange that.

Is recognition by the professional community important to you?

Yes, of course. We will take the Peter exhibition abroad. Although it’s technically difficult – we have meter-sized photos. But I don’t promote myself personally as a photographer: I don’t communicate with anyone in particular, I don’t like social networks very much. The community in England is very small. I don’t even know who’s shooting humanly here. In my opinion, the only really interesting photographer alive today is Michael Kenna. We are going to do an exhibition of it in St. Petersburg. Tim Rudman is a good landscape photographer who prints his own landscapes, but I’ve never seen his work live. I also like the work of the Russian photographer Sasha Gusev. But I don’t understand Martin Pare, who is popular in England.

What do you shoot most often yourself?

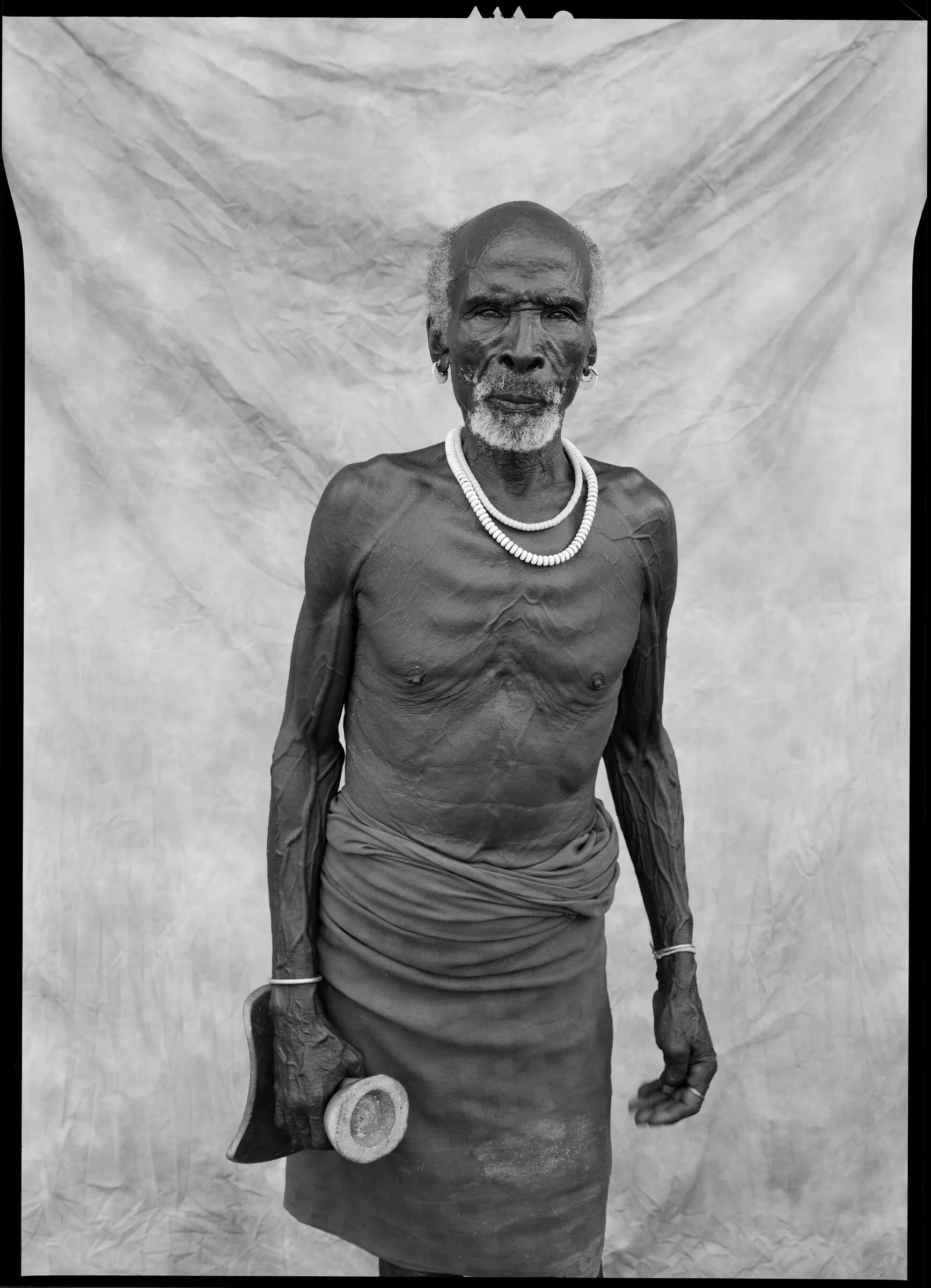

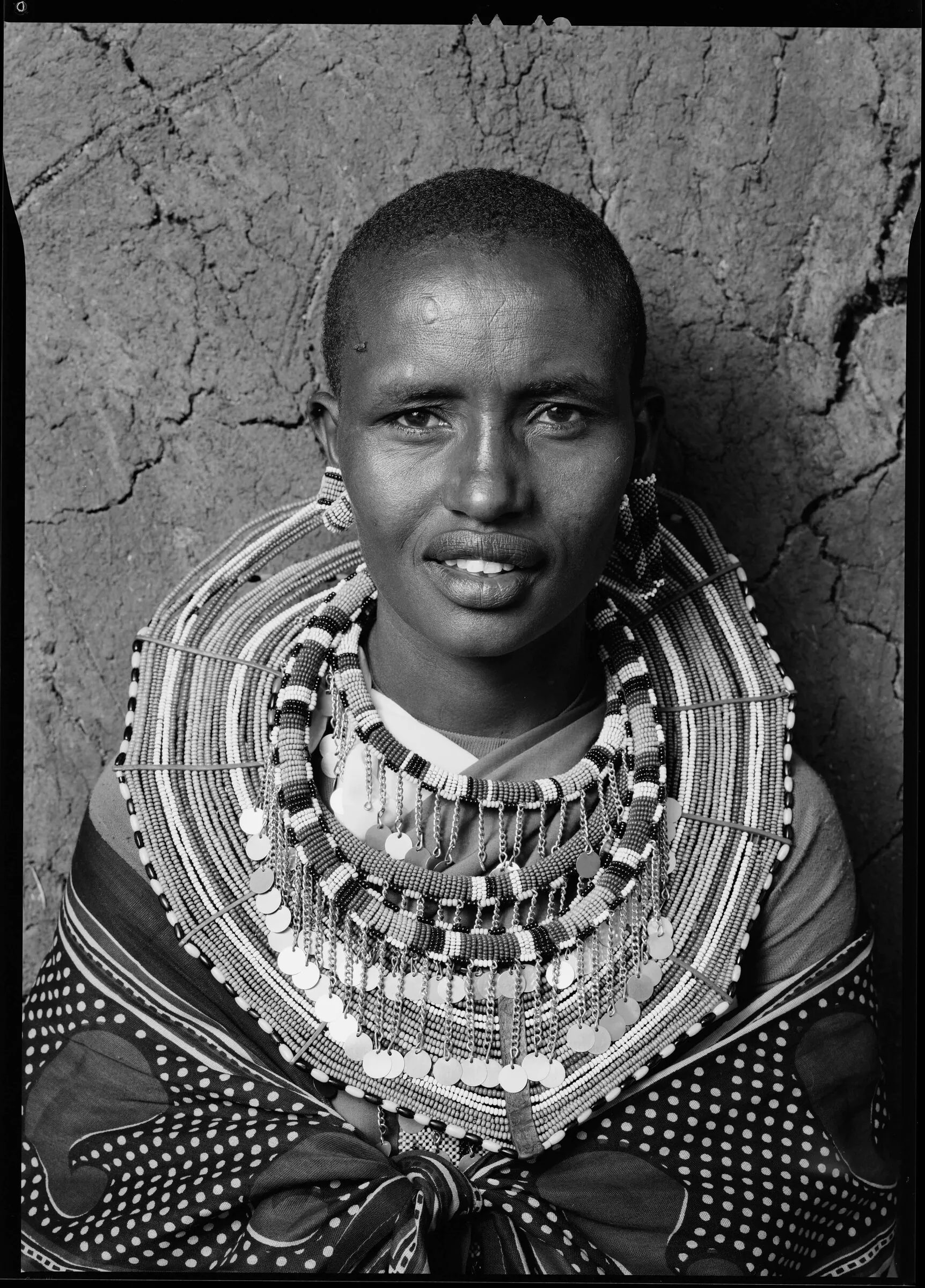

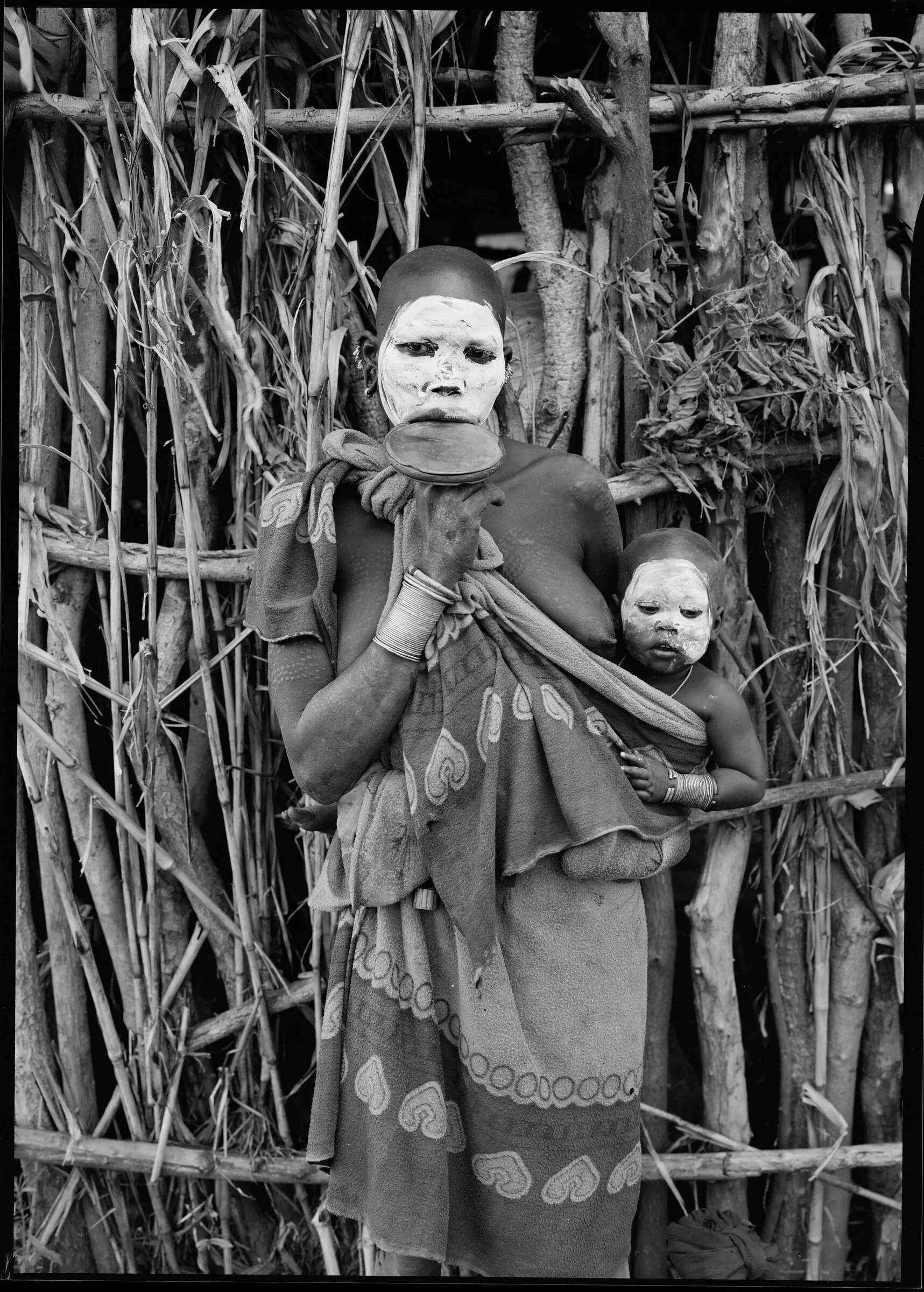

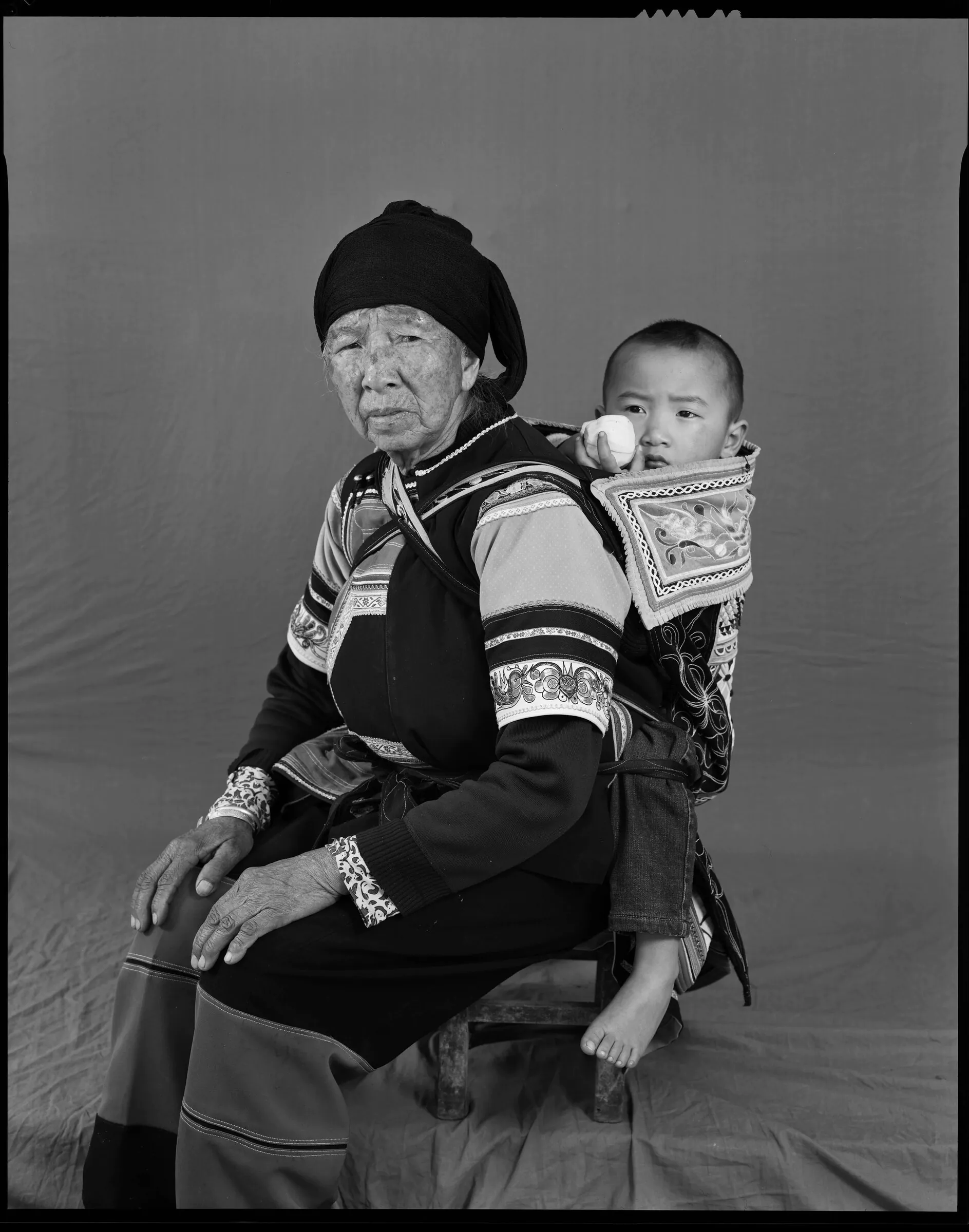

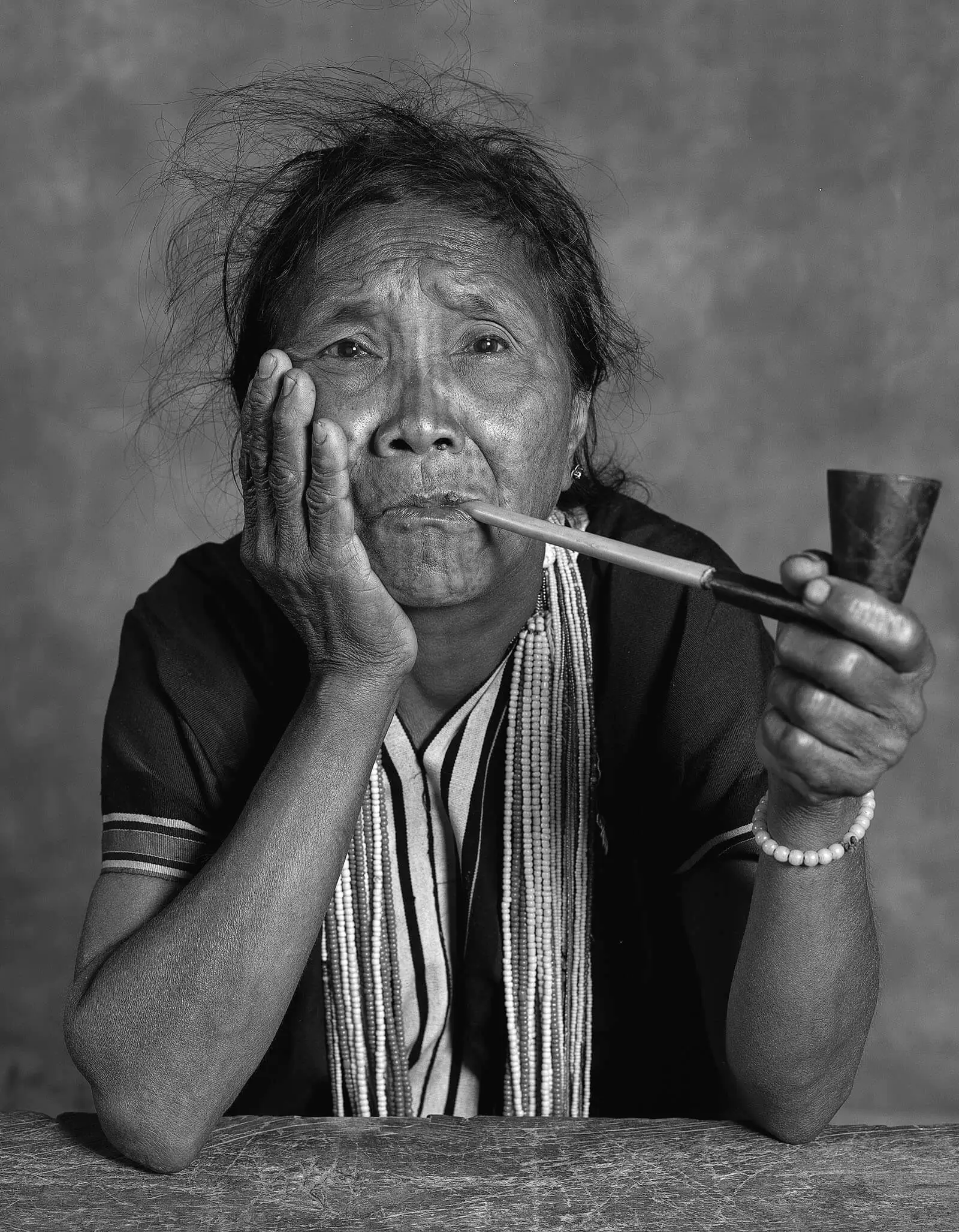

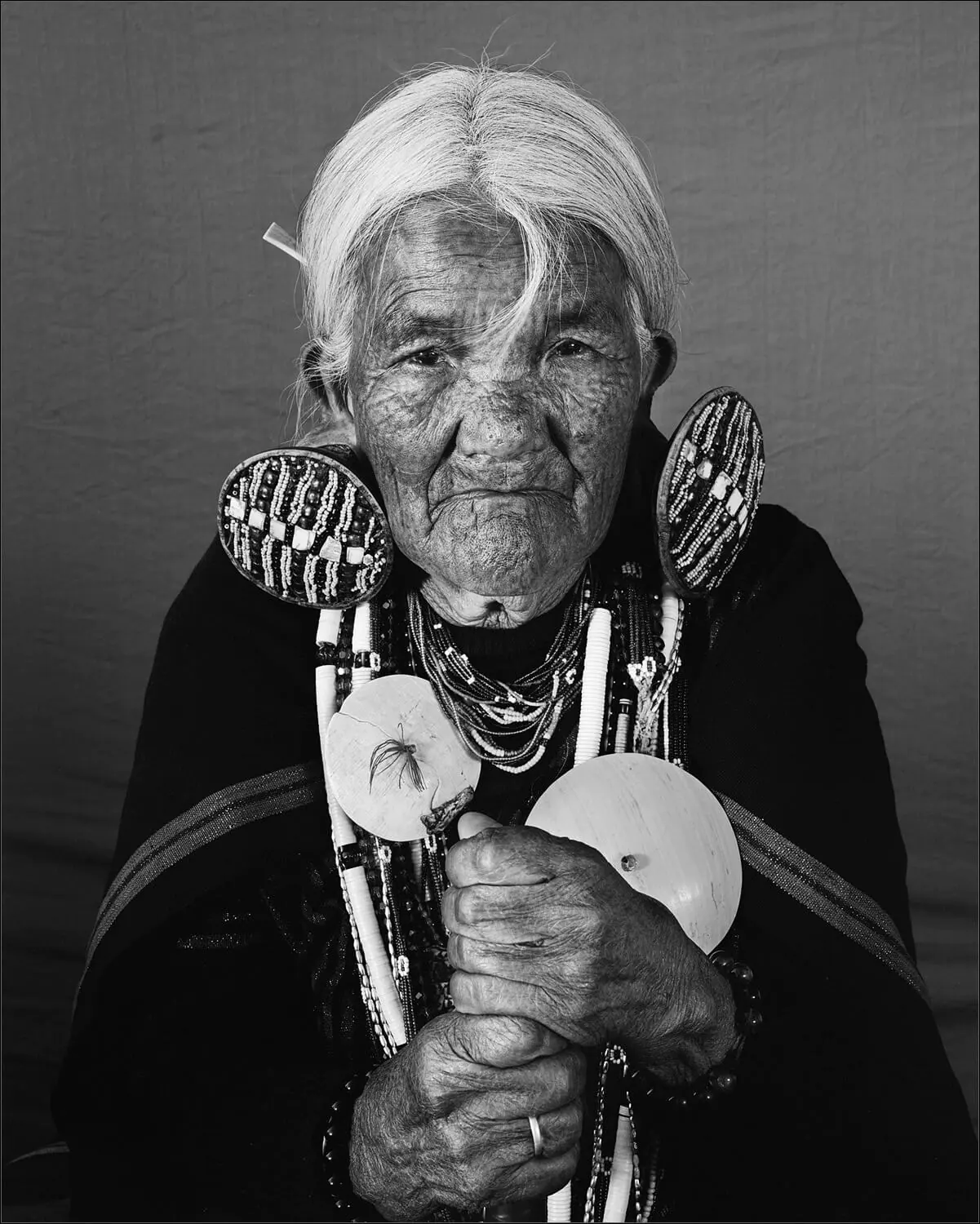

Now I and my Art of Foto colleagues are doing a big project – we’ve been shooting “Faces of the World” for four years now. We were in Papua New Guinea, three African countries: Ethiopia, Namibia and Tanzania, Burma and China. We recently spent a week in Yamal. We want to capture people who still live the traditional natural life of those countries, who have not yet been touched by globalization. It’s a completely outgoing nature. In the near future, the monks of Valaam. Next year, India and Latin America. Salgado, a famous traveler and an excellent photographer, visited many more countries, but always shot with a “watering can”, which, alas, affected the quality of the photos. Based on the results we will prepare an exhibition and a serious book.

You shoot on film. Don’t you think that film photography is also a passing nature?

Film or digital is a very popular discussion. I wouldn’t particularly want to contribute to it. Of course, color film photography is practically dead. In journalism, sports photography, fashion, etc., film has long had no place. But in my opinion, there is no alternative to film or analog processes in artistic photography. The main reason is that we see the world as analog, with smooth transitions of colors, shades and lines. And the figure is only an approximation of these lines. Naturally, we are talking about the final print. You can’t see it on your computer or phone screen. By the way, the analog photography market is slowly growing.

How do you deal with large format cameras when you travel?

That’s how we carry it – in hand luggage. Film, which is 10 boxes of A4 format, we also take in hand luggage. They are in protective cases, so every time they are forced to open them at airports during inspection, they start asking questions. Most people don’t understand what it is anymore. And also tripods, stands, backdrops and lights.

How many pounds is that anyway?

Probably 50-60 kilograms. You can’t fit it all in one car for a long time, you need at least two. On all trips we have a permanent team, without which it is physically impossible to cope with all this equipment.

You have wonderful portraits by artists Eric Bulatov, Oscar Rabin. Is there anyone else you dream of shooting?

I have a lot of plans, and among the already concrete ones are Ksenia Rappoport and Liza Boyarskaya and the Russian ballerina Natalia Osipova. I dream of shooting Shevchuk and BG, and we’ve practically reached an agreement with Makarevich. Of course, Gergiev and Eifman and Piotrovsky. For a long time I wanted to make a portrait of the Russian photographer Boris Plotnikov, the author of the iconic photographs of Vladimir Vysotsky. I don’t give up hope of making a good portrait of Chulpan Khamatova.

More interesting articles about Russians in London in our Telegram Channel

Photo by Vadim Levin (black and white) and Katerina Nikitina

More of Vadim Levin’s work right here:

Loading...

Loading...