More than fifty portraits by Hals were brought to London from various collections in the UK, the Netherlands, Germany, France and the USA. The exhibition will remain at the National Gallery until January 21, 2024, before traveling to Amsterdam and Berlin.

Frans Hals is one of the key figures in the history of painting. Perhaps no art history textbook can do without mentioning him. A contemporary of Rembrandt and Vermeer, he became famous for his ability to depict cheerful people – smiling, laughing, singing songs. The gradations of hilarity conveyed by Hulse are countless. His characters look funny, sly, gentle, confused, smug, carefree – each in their own way. This artist as no one else knows how to evoke empathy in the viewer, infect him with joy and make him smile with the citizens of Harlem XVII century as if they were your old acquaintances.

Hals’ teacher Karel van Mander wrote about the magical conquering property of laughter in the an instructive poem for young artists, “The Fundamentals of the Noble and Free Art of Painting.” However, portraying laughter and smiling in such a way that they are natural and do not look like a sour grimace or crying is a very difficult task. Although it was laughter, its nature and healing properties that were often discussed by philosophers, scientists and writers in the seventeenth century, few artists dared to paint laughing people.

Conceptually, the exhibition at the National Gallery offers no new clues to Hulse’s legacy and makes no claim to relevance. It is organized chronologically: it opens with the works of a young artist detailing the rich clothes of his clients, and ends with the late experiments in which Hals’ brushwork achieved a freedom comparable to that of the Expressionists. Between these two points, different facets of his art are shown: family portraits, group portraits of officers and important townspeople, and depictions of unknown commoners: children, actors, and musicians.

Many anonymous characters in Hals’ paintings are members of the Harlem Rhetoric Circle, which included the artist himself. The circle met on Saturdays, here they read poems, sang songs and put on plays. Theatricality is generally characteristic of Hals’s work. He loves to decipher secret symbols or portray his characters in active interaction. For example, Peter Cornelius van der Mersch, known for his ability to ridicule people, offers the viewer a smoked herring, recalling the Dutch proverb that to give someone a smoked herring meant to criticize them.

The curators claim that Hals has succeeded in taking the portrait genre to a new stage. His teacher Karel van Mander wrote of portraiture as a secondary genre, inferior to depictions of biblical or mythological scenes. The portraitist, according to van Mander, merely dutifully reproduces what he sees before him, without engaging knowledge or imagination. Hals’ portraits cannot be called mere reproductions of the model – there is a magic of life and stopped time in them. This magic is more important than the name and biography of the person portrayed. The section containing portraits of anonymous characters from the Rhetoric Society is like a banquet hall in the middle of a celebration: everyone is laughing, looking inviting and inviting you in with expressive gestures.

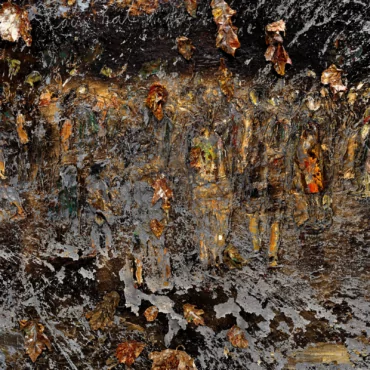

Hulse painted portraits very quickly. He worked in the technique of alla prima, that is, he did not make preparatory drawings, only outlined the basic silhouette with brown paint and over the top immediately painted a portrait. He could be very careful, writing out the texture of the velvet and the delicate pattern of the lace, paying attention to the way the fabric shone through the crimped collar or reflected in the gold chain. But far more often than not, Hulse missed details and painted as quickly as if his brush was rushing for time, afraid to lag behind and miss the movements of the restless Harlemians. This haste is easy to notice: in some paintings, unpainted ground, hair, mustache, a bundle of straw – everything is painted fluently, almost abstractly. Similarly, the folds of clothing and hands can be painted abstractly.

Despite their directness and vivacity, Hulse’s characters act according to seventeenth-century norms of behavior. A popular book was Erasmus of Rotterdam “On the decency of children’s manners”, which gave instructions on how decent to laugh, and how unacceptable: “Loud laughter and unrestrained giggling, rocking the whole body and for this reason called shaking, inappropriate. It is unseemly to make a roaring noise while laughing. It is rude for someone to open his mouth wide, wrinkling his cheeks and baring his teeth as if he were a dog. Indeed, in Hals’ portraits, only commoners and tipsy people bare their teeth, when the faces of honorable citizens and their wives usually show a smile. In an admonition to young painters, Van Mander wrote that if the artist depicts lovers, he makes their faces friendly and smiling, and when their feelings are especially ardent, you can add a red tint to the paint. Hals knew how to portray a smile without distorting his face, only adding a blush and making his gaze cheerful and radiant.

Great fame came to Hals in the second half of the XIX century, when the French artists who opposed the dry academic painting, recognized in him his predecessor. Haarlem became a place of pilgrimage, and the city hall opened two rooms with a collection of Dutch art and Hals’ works at the center of the exhibit. Gustave Courbet admired the paintings of Hals, Van Gogh put him on a par with Michelangelo, Raphael and ancient sculptors.

At the same time, the myth of Halsa was taking shape: stories of drunkenness were omitted from his early biographies and his celebrity was emphasized. James Abbot Whistler believed that Hulse’s works themselves showed that their author could not have been a drunkard and a cad. The artist’s fame faded in the twentieth century, when technical perfection, freedom and boldness of the brush gliding across the canvas no longer excited minds. The history of art was rushing forward, leaving Hulse behind, among the old masters. Today, when the succession of artistic revolutions of the 20th century has itself become part of the museum archive, the National Gallery invites us to look again at Hals’s work. These works speak the same language to us.

Loading...

Loading...