An international exhibition on propaganda techniques was recently held in London, – Brainwashing Machine. Your work participated in it. Please tell us more about it.

In my work, I wanted to show a cross-section of one society: many faces of people of different ages, religions, colors, genders… It is not completely clear whether these people are silent or screaming, or whether they are screaming inside but cannot say anything out loud. My mouth is not screaming or clamped shut, I am smiling. I am in prison, but thanks to this I am freer than many, because I am no longer afraid of being locked up.

Prison has made me a more diligent person – I can now persevere and painstakingly draw every detail, something I lacked before. This is one of the few works I was able to do with my new tools in prison.

I never wanted to be an artist and I don’t really devote much time to it, unlike music – it’s the only field I’d like to develop and be recognized in. But for some reason all my life I’ve been recognized as an artist.

The best works of mine that have been appreciated are the works that I created in five minutes. When I do something long and painstaking, most often I hear: “Well, yes, it’s beautiful” – it demotivates me a bit to develop in this field. But at the same moment I realize that people are most often attracted to my works by their naivety, their wrongness, my desire not to correct mistakes and not to see anything in creativity as a mistake in general. I believe that it is impossible to be wrong in creativity. The first time I was labeled as an artist was in 2014 when I posted a comic book, my little “Depression Book.” I posted it for my friends to understand why I struggle and sometimes can’t go to work even though I look healthy. Why I say at some points, “No, dudes, I’m dropping all my projects, I need time.” There was a mental stigma, and I was one of the first mental activists. This book immediately went viral, I was interviewed and they called me, “Sasha Skochilenko is an artist from St. Petersburg.” I thought, “Fuck, what kind of artist am I?”.

But eventually, when I went to prison, I became famous again as an “artist from Russia,” and all I could do to dispel myself was draw.

How did you create your artwork while incarcerated? What emotional process was going on inside you while you were creating your drawings?

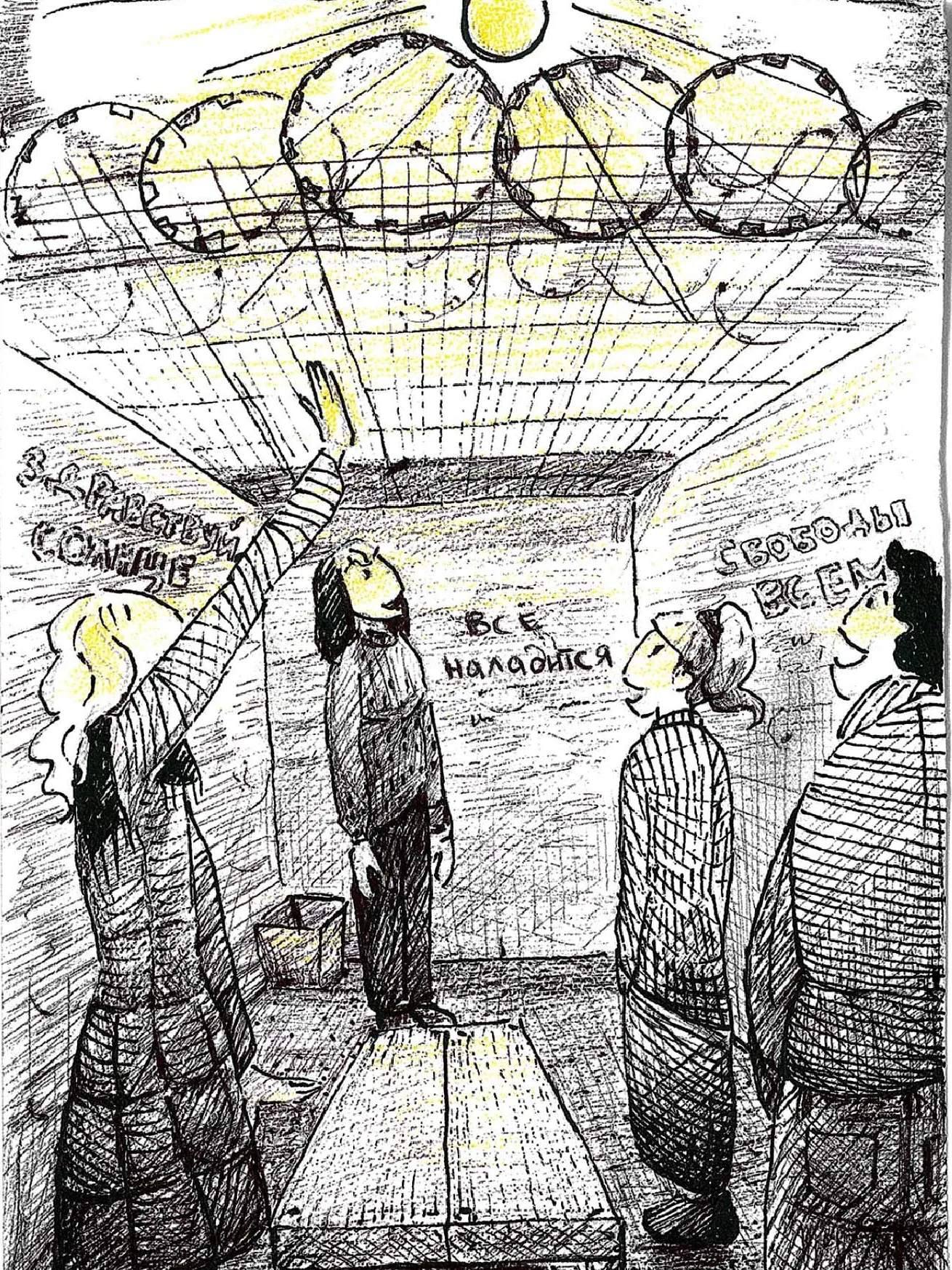

For me, creating art is definitely a state of comfort. Now, for example, I am in an art residence where I am simply provided with all the conditions. I divide creators into two categories: “singers of sorrow” and “singers of joy”. “Singers of sadness” are those who draw energy from the saddest and saddest of experiences. I am a “singer of joy”; I create my best work in euphoria. It was different with prison work: art became something that made me comfortable. Literally and figuratively, there were exhibitions in freedom, I became famous, and people sent donations. People now ask: “What can I do to help political prisoners?” and it’s very simple: money. Do you understand? Because money means doctors and medicines, money means food. And I soberly realized that I had to keep creating in order to survive morally and physically. I drew my way out. I have this trait – if you fail at something, it means you haven’t tried hard enough. You can put in all your irrational strength and end up achieving even the impossible. Which is essentially what happened. As for the creative process itself, yes, it was quite difficult – colored pencils were forbidden in the pre-trial detention center. They took them away, they took away my flute – I thought I would play. I had another bag with “forbidden goods” on my bag, there were flutes, colored pencils, but they accidentally missed a yellow pencil. Also, you couldn’t bring in a sharpener – it just wasn’t there. So I was constantly sent simple pencils – there were “a billion” of them. In the beginning it was very difficult: I had blue and black pens, black and yellow pencils.

If you remember the very, very first drawing where the girls are on a walk and I’m reading letters. Officially those are some of the very first drawings. I had to, with a very small arsenal of creative tools, keep creating from the resources available. You probably know as a creator that, in fact, limitations breed a lot of creativity. At one point, I managed to sneak in a few colored pencils. And a sharpener with expertise, too. A sharpener! I brought some watercolor pencils, and with their help I got those drawings in blue and brown tones, where, for example, I am sitting in a convoy and also a girl with a pacifik.

I always had to hide the extra pencils. I had to hide the drawings too and pass them “out” in an interesting way. Do you realize how much you had to do to make those drawings see the light of day? I think that’s where their value lies. First of all, I’m educating people about what goes on in a women’s prison, it’s a very closed place. They’re very strict about “keeping a low profile”. The warden once said to me: “Happiness loves silence.” Ah-ah-ah-ah, well, happiness is like that… Then, later, almost a year later, new TACs (internal regulations) came out. And pencils could be handed out in six pieces. I was given eighty pencils in six pieces. Eighty pencils are much harder to hide than five or six. So I had to hide them. I’ll tell you how. We were given these utility kits, and they had really stinky laundry soap in them. I can’t even put into words what it smelled like. I would stuff the space under the nightstand with this stinky soap and then I would stuff the pencils in the corner. And if one of the employees took something out from under the nightstand, it was soap, and they had enough – they didn’t get to the pencils.

Then I had black pens, I liked to draw graphically. I had “all the time in the world”, and my drawings are very different from what I drew in the wild. In the wild, you drew something and ran off to do music. Out there, I could spend all day drawing. Then I learned to dilute gel pen ink with water, mixed ink with pencils. I had one blue liner that apparently had alcohol in it – when I diluted it and put it on paper, it gave a very interesting glare. Then we learned that you could pass on purple pens. I was bought a purple set of pens in different shades. My painting of faces was done by them – it’s a drawing about freedom of speech. I was by then quite mentally tired of having something taken away from me periodically on search. I was on my knees begging to keep my paintbrushes. That’s what my art was made of – very difficult and hard. It seems to me that art often thrives in a restrictive environment, not where it’s nourishing and good. Art for me started to happen in a period of crisis, and I realized that if an artist is always in comfortable conditions, sooner or later he will have nothing to create from.

The experience of prison was important to me as an artist. Prison is a library of human destinies. It’s where we talk about really important things, about huge universal problems. I remember we used to watch TV shows sometimes, and in one of them a man was very upset that he had lost. My roommate and I looked at each other, and I thought, “*fuck, these are the problems people have…”. In everyday life, you think something like this is a huge problem, but it’s really nothing. Life or death, freedom or unfreedom, those are the real problems.

In prison, you see people’s emotions in the most difficult circumstances, hear their thoughts about what is happening to them and around them. It’s a tremendous experience from which to create. I believe that art of great power is created from just such situations. It gives hope where it seems to be rationally gone. That is why art is so important where there is no way out.

I would show my work to other inmates and they would say, “Wow, that’s so cool.” I think it really meant something to them. My drawings were about life, about experiences, and I felt that they understood that.

Did you have any doubts about the price tag action? Did you think about the consequences, or was it an expression?

I understood the risks, but I thought it was at most an administrative offense. I was prepared to sit for fifteen days.

Stop? No, there was no such thought. Sonya begged me to stop, but I had no reason to. I was doing it for me, for my conscience. Price tags were the last thing I’d ever be arrested for. I shoved them everywhere, but they only found five.

Tell me about life in prison. What is life like there, what does it consist of?

Let’s start with the difficulties, the mundane. When you think of a prison, you imagine it’s a dungeon with spiders, and it is. In Russian TV series it’s very well represented, even the Moscow pre-trial detention center isn’t much different. You are locked up every time, but you try not to think about it, even though it’s violence that is done to you every time, but you try to disconnect from it.

There are regime cells in the pre-trial detention center, and I went there first. People take turns going to the toilet. And everyday life consists of cleaning all the time. Many women in prison have a neurosis of cleanliness – OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder). Because they find themselves in a situation where they can’t control anything, they try to control what they can control. Some feel like dust is everywhere, some dust the joints of floorboards with their bra bones. They wash the walls every week. How often do you wash the walls at home? Cleaning is also used as a form of violence. I know some cells where if the women’s hands were not red and blistered after washing the floor, they were told, “You didn’t wash well”.

Thank God, I was quickly transferred to a two-person cell, because I complained to my lawyer, and we were publicizing the whole thing in the media. The staff told me: “It will only make things worse for you if you complain. But, in fact, it’s only bad at first. If you go this way, sooner or later you will be respected. There is another way – to cooperate with the “trash”, to fight for some very small privileges, to tolerate. It’s all about being patient and waiting all the time. For example, waiting to be let out of the exercise yard. It’s winter, it’s freezing – minus 25 degrees and you’ve been forgotten in the yard for three hours. And knock, don’t knock – when the employee comes, he’ll open you up. He won’t even apologize, he’ll say, “I had a lot to do.” It’s the same with going for a walk: you can get dressed and stand waiting for hours, but the door still won’t open.

Then it’s the waiting for the trial: they don’t bring you to the trial itself, they bring you in the morning, and you sit and wait.

And every day is like the day before. But I decided to myself that the people who put me in prison wanted me to live a very bad life. I would live a good life to spite them. I made something good out of my life in prison, trying to find pluses. I learned to enjoy the simplest things. I liked to lie on my jacket on the concrete floor and watch ants crawling from under the broken slab. Sometimes very small plants grew from underneath it. Big plants were ripped out.

Joy is in the small things: today I had a delicious coffee, today I went for a walk and the sun was shining, today I met a lawyer, today I had a very interesting conversation with my neighbor. If you don’t cling to these things, you are “dying.”

My point is that prison is not the end, there is life there too.

I was not allowed to bring drinking water at first because there is no drinking water in the prison. The simplest thing is not there – there are empty barrels for drinking water. I always asked: “It says there that you provide us with a drinking water tank”. I was answered, “No, it says we provide you with a drinking water cistern.” It was believed that we were supposed to boil tap water and pour it into these barrels. When I told this to the Human Rights Ombudsman, she was a**holes, she didn’t even know about it. About the fact that there is no water in the pre-trial detention center for people to drink. Only 100 milliliters per person – breakfast, lunch and dinner. Three hundred grams of water per day for an adult.

I tried to help people, and it brought me joy. People gave me a lot of resources – money. Neighbors came to me from big cells where they were abused. When a “senior” – a woman who cooperates with the operatives – could forbid people to eat when they wanted to, or to go to the toilet. They would come to my cell and ask: “Can I go to the toilet?”. I always answered that everything was allowed here, I tried to maintain an atmosphere of freedom in the cell I was living in. And you know, after a month these people blossomed, they went from deep depression to a more or less normal state, they started fighting, laughing. I always said: “You can do whatever you want when I’m sleeping – I have good earplugs.”

I had a neighbor, she was beaten by her husband on the outside. She lived with me and at the end she said: “I noticed that you love yourself very much. I also want to love myself and I want to break up with my husband if he doesn’t stop.

But anyway, I did two performances: imprisonment and release from prison. The thing is that being in prison was my creative will. I could have pleaded guilty at any time and ended up at home, but I chose the truth.

So you’ve had different people move in with you?

Yes, I lived with a total of twenty roommates. Some came and went quickly – some to the zone, but, strangely enough, most of them went free. Not on acquittals, of course, there are none in Russia, but, for example, on suspended sentences, etc.

And I realized that good comes back, sometimes in very unexpected ways. Evil, unfortunately, does not return.

Tell me about the people you met there? How did they treat you?

While you are a newcomer, everyone is wary of you. But when you have been there for a few months, the staff start to turn a blind eye to some things. It sounds strange, but over time the attitude changes to a rather friendly one. At the end of my incarceration I could drive to court and every staff member I met would say, “Oh, hi, how are you doing?” and mostly they were always asking, “When are you going to be released?” A lot of people thought I was innocent. Some employees came out of their cells and said: “I respect you very much, I admire your deed very much. I would do it myself if I could. Prisoners mostly said only good things about me.

If you’re a famous person, bad things will be said about you.

I collected various interesting gossip about myself. One day I was assigned an Uzbek girl, Roza, and after a month of living in my cell, she said: “Sash, I want to confess something to you. They told me you’re a lesbian.” I said, “Well, yes, I am.” Someone told her that I rape all my neighbors, that I get deliveries from the restaurant and that I have “intimate tobacco.” What they do with “intimate tobacco” I don’t know. Also, that I have a “machine” – some kind of electromechanical strapon to rape everyone. I laughed for about twenty minutes after that.

It turned out that it wasn’t funny at all, because for the first month while she lived with me, she couldn’t sleep, afraid that I would come down from the bed and rape her. Moreover, every time I wasn’t in my cell, she would look for that machine and there was no way she could find it. When I laughed, she looked at me with such naive eyes and said, “Are you sure you don’t have this machine?”.

There were very different women sitting with me. Prison is a huge cross-section of society. I went to prison with three hundred rubles in my pocket. And once I met a woman who had eight hundred million dollars worth of property seized. She had a successful business, and she didn’t share it with anyone. There were a lot of people who were in jail for fraud. There are very rich people, there are very poor people. There are people who live on the street, and they say it’s much better in prison. People of very different nationalities. I lived with a Gypsy woman, and my last neighbors were Uzbek women. I learned a lot about Islam, about Uzbekistan. It was very interesting for me to meet them, to learn more about them and their culture. And to think that all officers and policemen are complete bitches is also wrong. Operatives and investigators – yes, they are all complete bitches. There are also cruel people among the staff, and sometimes there is a feeling that they came to prison to satisfy their complexes. And there are really human, adequate people who made my imprisonment a little softer, a little happier. They could talk to me, some of them even supported me.

I learned a lot about them. Police and FSIN officers are like a separate caste in Russia today. And it is very interesting what they live and how they live. To understand how to change this police regime. To understand what they want more than to serve Putin.

And what do you think they want more than to serve Putin?

They want money. They’re all sure they don’t get enough. They have tons of social benefits: the state can pay for part of the purchase of an apartment, they can put a child in a kindergarten without waiting in line. It’s a huge social package. Basically, these are people who want a good stable life. And all their conversations are only about how much and when they were paid, how much someone overworked. And the main thing is how much time is left until retirement, because they are retiring early.

They want to live comfortably without doing anything. Their life is mostly subject to orders, they don’t have to think about what to do.

Money is such a thing, it’s never enough. People build palaces that no one lives in. It can’t be satisfied.

What did you do before the war?

At the age of twenty-seven, I decided to quit a stable job that brought in a good income but took all of my creative energy.

At the same time, I graduated from university with a red diploma and dreamed of an academic career. The social elevator “decided” to take me upwards, but I arbitrarily pressed another button and fell into the St. Petersburg underground. I had no money at all. I decided that I would rather die than do something I didn’t want to do.

We lived with Sonia, I lived on the edge. Sometimes there was no money at all, and I had to take on some odd jobs – construction, restoration, stacking boxes, babysitting. It took energy, but it didn’t take away the creative energy, thanks to which I could create. I spent all my time creating. I was very poor, but very happy.

I never saw the money people sent me in prison.

My life before the war is the life of many independent artists in Russia. When to create if you go to a stable job? Half an hour before going to bed?

And inspiration is such a thing, it can get you up at two in the morning. I wanted to have “all the time in the world” to create. But it was literally painful to walk – I had flat feet and no money for orthopedic shoes or insoles. I was bleeding my feet, I had blisters growing on my feet. And I was walking with a backpack that weighed 16 kilograms while I weighed 45 because I was melting – there was no money for food. When I got to prison, I realized that it was a time to think about how I was living.

How do you remember the day of the exchange?

The exchange happened unexpectedly, I didn’t fully believe it. The staff were always lying and it felt like we were going to be shot in the forest.

Out of this whole story, everyone is very interested in the moment when I realized that I was being changed. This realization happened gradually and is still happening.

Tell us about what life with fame feels like? What are you doing to cope?

I, for example, try to use my smartphone less, as I realize that sooner or later I will be sucked into this digital world. I try to leave it at home sometimes. Since I’ve become very famous, I’m afraid to go there. I try not to read comments, although I have seen negative ones and I can say that they don’t really touch me.

I have already grown a huge ego due to fame and I’m afraid to feed it.

What would you say to people who want to continue doing activism in Russia?

First, let me say that I am not an activist. I am an artist who has responded to the challenge of modernity.

I also want to say that prison is not the end, in Russia it is very much feared. The worst thing is that this fear is passed on from generation to generation. In the thirties, going to prison meant death, and I think this fear is still alive.

Prison is not the end. If you want to fight, fight. I was told that I couldn’t stop the war, but now I’m in jail for it. I couldn’t stop the war, but a lot of people realized that 7 years for price tags is something else. I think people were inspired by what I did and started to realize that what was happening was not normal.

Maybe fighting and protesting won’t help, but we need to change people’s minds. They are severely depressed if they are ready to go out and kill. If this is changed, something might change.

The only thing I would like to add is that even the smallest deed can make a difference. Don’t be afraid to do even small deeds!

What are your plans for the future?

First of all, I want to live, love, ride in the woods. But I realize that I will do charity work related to political prisoners.

And, of course, getting married. We’ve been wanting to get married for a long time. I realized in prison how important it is. If she were my wife in a country where same-sex marriage is recognized, she would be able to visit me in the pre-trial detention facility, but in the colony, only relatives are allowed long-term visits. But unfortunately, Sonia is a nobody in Russia on her passport. And in Germany we realized what privileges marriage gives us. For example, I can transfer an unlimited amount of money tax-free – a family transfer.

Or, for example, only relatives can come to the intensive care unit.

Books in support of political prisoners can be purchased at the ZIMA Shop .

Loading...

Loading...